Community Trust and Impact

Why Stony Brook University’s research and support of Long Island residents is critical to the region's battle against COVID-19

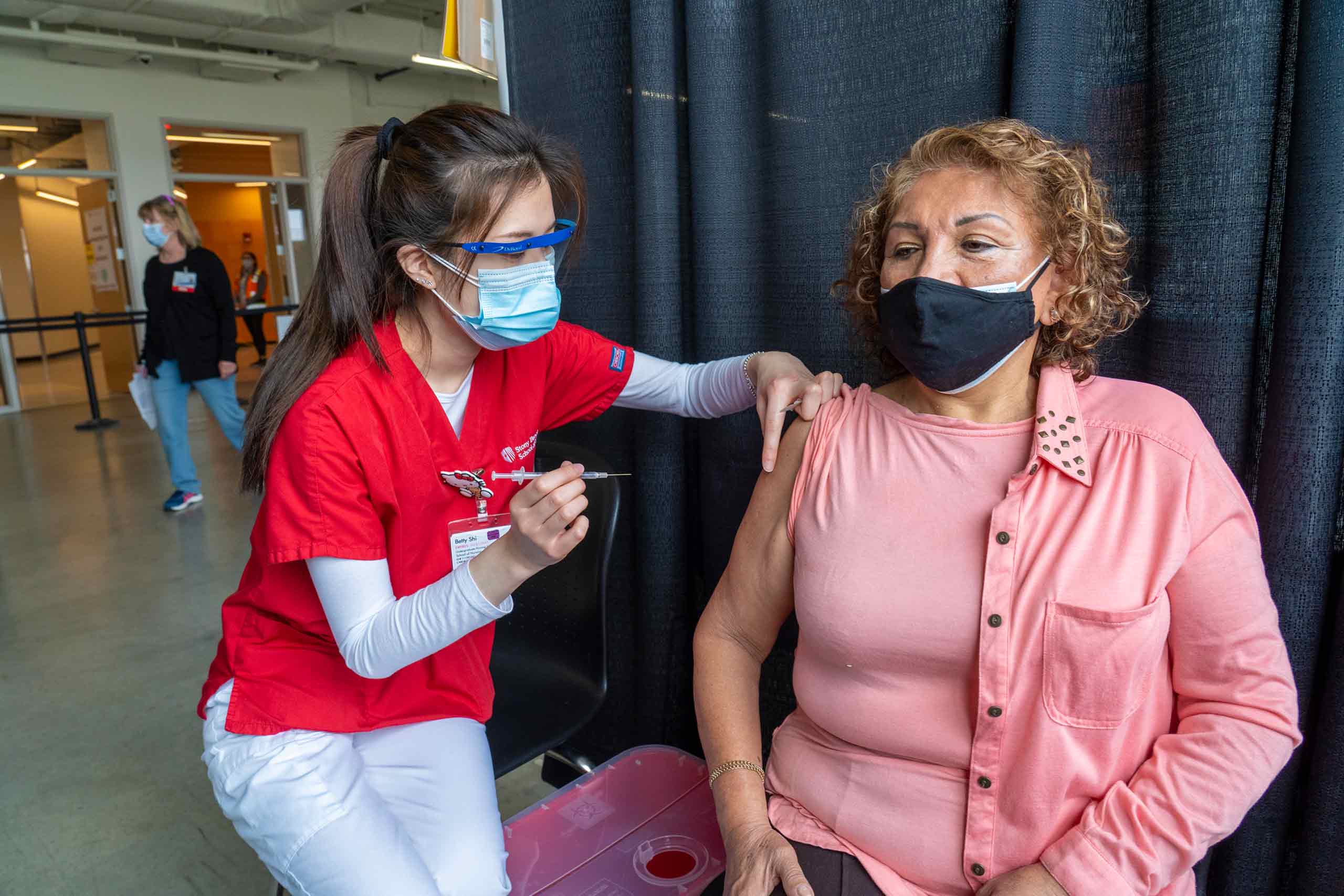

Early this April, Margaret McGovern, MD, PhD watched as appointments at three mobile vaccination pods for 4,500 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine booked up in 23 minutes. The demand was encouraging and she couldn’t help but feel astonished by all her colleagues at Stony Brook Medicine had accomplished in the year leading to this point.

As the vice president for health system clinical programs and strategy, Dr. McGovern oversees Stony Brook Medicine’s vaccination program, which inoculates thousands of patients every day through its partnership with the New York State Department of Health, the system’s hospitals and affiliated physician’s offices or mobile pods.

She’s also been in the trenches of the hospital system’s COVID-19 response since last spring. That included overseeing the creation of an incremental 350-bed facility to manage the surge of patients at the beginning of the outbreak; ensuring that long-haul patients receive care for kidney, lung and neurological damage; and encouraging underserved communities like the elderly, migrant workers and the developmentally disabled to get vaccinated.

Whether it is working with local clergy and tribal leaders, translating vaccine information into Creole and Spanish, or developing special materials to reach people who are nonverbal, Dr. McGovern’s team is building on Stony Brook University’s history of serving Long Island through research and services that benefit local residents, particularly in communities of color.

Stony Brook’s mobile dental clinic targets at-risk populations on Long Island.

Stony Brook’s mobile dental clinic targets at-risk populations on Long Island.

The Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science helps scientists interact with laypeople.

The Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science helps scientists interact with laypeople.

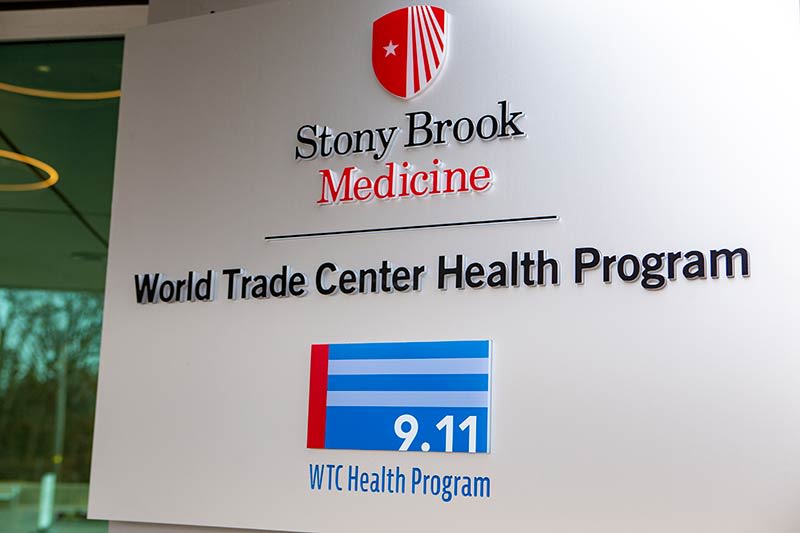

The WTC Health Program serves thousands affected by 9/11.

The WTC Health Program serves thousands affected by 9/11.

Bringing Care to Local Residents

As part of that mission, Stony Brook supports communities across Long Island with medical services like its Mobile Mammography Van, which ensures that every local woman, age 40 and older, who needs a mammogram can access one, even without a prescription. Its Mobile Dental Clinic brings dental students and professionals directly to underserved patients at locations like homeless shelters and elementary schools.

Engaging with the local community through both medical services and research is aided by the work of the university’s Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, which helps scientists and medical professionals understand their audiences, so they can communicate with them more clearly and relatably. The center, which opened in 2009, is a collaboration between Alda, Stony Brook, its school of journalism, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, which is managed by a team that includes Stony Brook.

Supporting First Responders

After the September 11 attacks, Stony Brook recognized the unique needs of first responders, many of whom live on Long Island. Stony Brook developed the WTC Health Program, which serves more than 10,000 patients living with cancer, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, pulmonary conditions and other diseases through a collaborative care model.

In addition to providing care, Stony Brook is conducting critical, federally-funded research. “Even though this happened quite a long time ago, we’re still learning what those long-term impacts are,” says Richard Reeder, the vice president for research and operations manager for Stony Brook’s Research Foundation. “This program monitors individuals who were impacted and provides healthcare when they need it,” he says.

Aiding the Coastal Community

In addition to providing medical care to local residents, Stony Brook is also conducting novel research into local environmental challenges like excess nitrogen in the area’s groundwater.

Through Stony Brook’s Center for Clean Water Technology, researchers are developing septic systems that either eliminate or greatly reduce nitrogen, helping protect precious groundwater.

Scientists at Stony Brook’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences are also conducting research that could benefit the local fishing industry, including restoring local oysters and using shellfish to improve water quality.

Reeder, who is also associate vice president for laboratory affairs at the Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, says the university is also working with developers to solve technical hurdles in establishing offshore wind as a viable clean energy source for the region, while ensuring little impact on the environment.

Long-term Relationships Build Trust

The longstanding relationship that has proven beneficial to the local community has helped Dr. McGovern and her team overcome challenges like vaccine hesitancy.

“People have big concerns about the vaccines being distributed under an Emergency Use Authorization, especially in the beginning. Others expressed concern about conflicting guidance between the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization for pregnant women,” she says. “And it remains to be seen whether the government’s decision to halt Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 shot will amplify skepticism among those reluctant to get vaccinated in the first place. No matter what, viewpoints must be respected and talked through.”

“These are our patients who we’ve served through primary care physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners.” Still, she says they would not have been as successful without the support of faith-based organizations and other community groups, with whom Stony Brook has a history of collaboration. “I don’t think we could have done it alone through a typical medical model,” she says.

Vaccine pods, for example, are an innovation for Stony Brook Medicine. For while the system features 236 outpatient locations, Dr. McGovern says it’s critical that they reach out to the homebound and into Spanish-speaking communities. Vans carry supplies to firehouses, rec centers and senior housing facilities, all of which must have sanitary facilities and access to reliable WiFi, which is critical for reporting requirements. The smallest pods they’ve deployed vaccinated 250 people, but the larger ones can serve up to 2,000.

Dr. McGovern says she’s been pleasantly surprised by people’s willingness to return for their second doses. “If you look at other multidose vaccines like hepatitis, people frequently drop off,” she says. “I’d say it’s rare that we lose an individual who needs a second dose.”

Stony Brook’s medical services benefit local residents.

Stony Brook’s medical services benefit local residents.

Assessing long-term needs

Once the vaccine distribution push ends, Dr. McGovern and her team will continue to focus on the long-term needs of COVID-19 patients. “It’s abundantly clear that we needed a post-COVID follow-up program,” she says. Stony Brook’s multidisciplinary team is treating lingering problems felt long after patients have recovered from their acute illness from the virus. “The whole medical community is learning about this,” she says. As patients enroll in the clinic and grant permission, Stony Brook is gathering information that will contribute to ongoing research.

“When you look back, it seems like longer than a year,” Dr. McGovern says. “And when I think about all the things we did, how quickly we did them and how fast we had to adjust, pivot and change, based on circumstances, it’s remarkable.”

This content was written and provided by Stony Brook University. The editorial team of Inside Higher Ed had no role in its production.