Full Speed Ahead

SUSTech’s higher education reform poised to make China’s high-tech sector better and smarter

There’s speed, and then there’s Shenzhen speed.

In just four decades, the former Chinese fishing village of Shenzhen has grown to more than 17 million people and become home to some of the world’s most important technology companies.

The Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) was founded 11 years ago in Shenzhen to provide knowledge and home-grown talent for this high-tech boomtown. Total enrollment already has topped 7,000 students, and SUSTech is already incubating new academic ventures that it will spin off into other universities within the city.

Perhaps more impressive than this rapid growth is how SUSTech is achieving these goals. The university has brought an innovative approach to Chinese higher education, especially in engineering and design disciplines. These academic reforms emphasize interdisciplinary projects, hands-on learning, innovation and entrepreneurship — elements normally absent from traditional Chinese universities. SUSTech faculty also work closely with local industry partners to ensure the region’s economy continues to grow and evolve.

“Shenzhen is the center of manufacturing for the future,” said Thomas Kvan, founding dean of SUSTech’s School of Design. “We need to look to the future to frame our education.”

Reforming higher education in China

The term “Shenzhen speed” was coined during the construction of a local office building. The 50-story building went up at the rate of one story every three days — an impressive pace in skyscraper construction — and was the tallest building in China when it opened in 1985.

Shenzhen’s growth has continued unabated since then. It’s the second-largest city of the Greater Bay Area, a megalopolis of more than 70 million people along China’s southern coast that also includes Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Macau.

Three of Shenzhen’s pillar industries are global logistics, finance and financial services, and cultural and creative industries. Shenzhen is best known for its fourth pillar: cutting-edge technology.

Dubbed China’s Silicon Valley, Shenzhen is home to thousands of tech companies — from start-ups such as Aftershockz, the innovative headphone maker, to giants such as telecom company Huawei, the world’s largest telecommunications equipment manufacturer; internet and gaming company Tencent, which developed the hugely popular WeChat app; and DJI, which dominates the global aerial drone market. Most of the world’s Apple iPhones are made in Shenzhen.

The municipal government founded SUSTech in 2010 as an experiment in higher education reform. Rather than teach by rote memorization using a standardized curriculum along the traditional and separate tracks of science and the arts, this publicly-funded research university would borrow ideas and methods from the world’s best universities in the United States, Europe and elsewhere.

Most importantly, this new university would stress innovation, collaboration and project-based learning. Students would get a well-rounded international education: Classes in both science and the humanities are required, and courses are taught in English.

Two SUSTech divisions in particular — the School of System Design and Intelligent Manufacturing (SDIM) and the School of Design — were created to fuel Shenzhen’s industry with new ideas and talented people who can find creative solutions to key technology and business problems.

SUSTech professors already have created 40 start-up companies, and the university operates more than 55 research labs jointly with local companies. This cooperation is vital: SUSTech faculty are able to transfer new technologies to the marketplace, and the university is producing graduates who are starting their careers with local companies.

“The reason we’re conducting this kind of reform here is because we see there is an increasing demand from the companies — especially those unicorns, innovation companies and other high-tech companies here in Shenzhen,” said Xiong Yi, an assistant professor of system design and intelligent manufacturing. “They have a high demand for this kind of talent.”

Developing capabilities

When Hong Xiaoping worked for a Shenzhen tech company, he recruited students from top universities. After about six months, some students were still struggling to adapt to corporate life. Hong found that the students who succeeded were creative and independent thinkers who could define a problem, apply the right knowledge to solve it and prevent it from happening again.

That’s a lesson SUSTech took to heart when it launched SDIM in 2018, around the time China rolled out its New Engineering Education reform initiative to modernize how engineering is taught. At SDIM, traditional lectures are out; hands-on learning through projects and group work is in.

“Knowledge changes all the time,” said Hong, an assistant professor of system design and intelligent manufacturing. “Capabilities should be developed.”

The school — which offers bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral programs — is built on a foundation of engineering and industrial design with an eye toward smart manufacturing. It also incorporates elements from many other disciplines, including materials science, electronic engineering, computer science and advanced manufacturing.

What undergraduates learn in the five classes they take each term is applied to a semester-long project. Professors give students weekly feedback on their projects, grading them on how much information they’ve learned and how well they’ve developed soft skills such as motivation, thinking skills, hand-on skills, communication and responsibility.

“With student projects, we really don’t care about whether the final demo succeeded or not,” Hong said. “We do care about their progress every week and what they have learned and what they have come up with.”

Faculty use class time to provide a knowledge framework — how students can find information they need for their projects — and help students with problems they identified in their weekly reports. At the end of the semester, SDIM students don’t sit for an exam. Instead, they do a presentation on their project that emphasizes what they have learned and how they’ve developed. It’s designed to be a dynamic process, Xiong said.

“It’s not like we have a plan and stick to the plan,” Xiong said. “We have to adjust what we teach based on their feedback.”

Design School students work alongside a local bicycle manufacturer to design handlebar grips.

Design School students work alongside a local bicycle manufacturer to design handlebar grips.

SDIM's Da Vinci Challenge Camp 2021 involved teams developing future cities concepts.

SDIM's Da Vinci Challenge Camp 2021 involved teams developing future cities concepts.

SDIM students' project presentations allow them to demonstrate their hands-on learning.

SDIM students' project presentations allow them to demonstrate their hands-on learning.

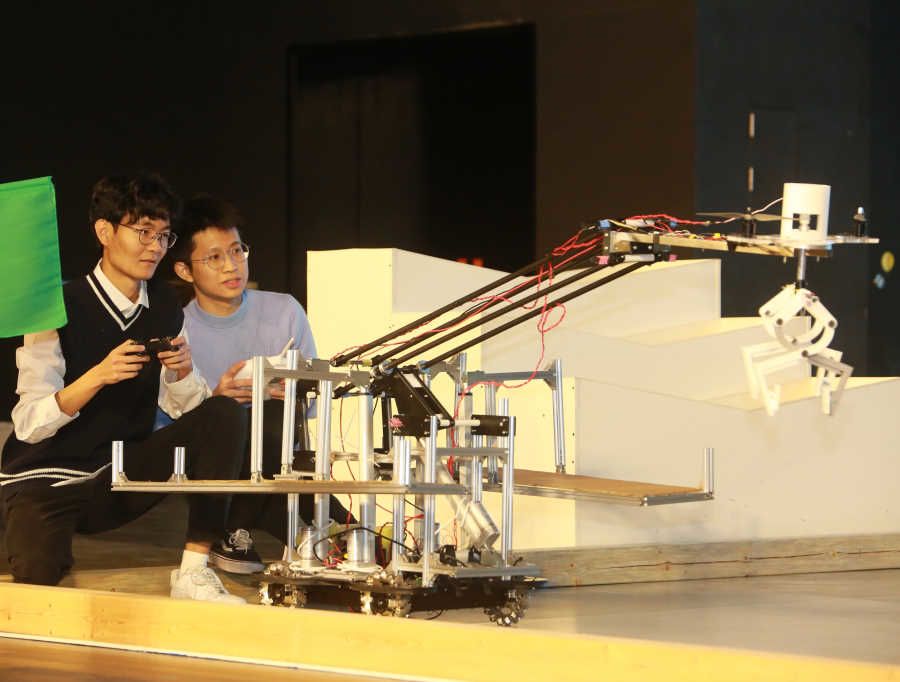

Video featuring SDIM's ARTINX student robotics club

Video featuring SDIM's ARTINX student robotics club

To tighten its connections to industry, SUSTech has recruited senior industry leaders to its faculty. Company executives and chief scientists regularly visit campus to lead seminars and give lectures, and students get to tour their manufacturing plants. SUSTech and DJI, the drone manufacturer, co-sponsor RoboMasters robot camps for high school students.

To help recruit the next generation of engineers and designers, the school invites high school and undergraduate students from around the world to campus for the six-week summer Da Vinci Challenge Camp. And once students enroll at SUSTech, they can join the university’s ARTINX Society robot-building team, which shared first prize in the national tournament finals in 2021.

Group activities — especially the projects — are the key to these engineering reform efforts at SUSTech.

“We use these well-designed projects to motivate students and let them really learn by themselves,” Xiong said. “These projects give them the knowledge framework and, more importantly, help them improve their capabilities.”

Building the creative class

SUSTech’s School of Design is even newer than SDIM — its first 18 students enrolled this fall — but its contributions to the regional economy will be just as significant.

Traditionally, Shenzhen companies have brought in designers from other parts of China and around the world. SUSTech’s new design school gives Shenzhen companies a local source for design talent.

The school offers studio-based instruction in five key design areas that cross multiple disciplines: objects; wearables, which includes high fashion and accessories; experiences, such as watching TV or playing video games; interactive, where people engage with technology and systems with each other; and environmental, which encompasses interior and landscape design.

So how does this work? Consider a great video game, said Kvan, the school’s dean. It must have outstanding digital media, interaction and environmental design. If the game is a success, designers will make officially licensed products to be worn, displayed or played with.

School of Design students also will learn cultural competencies — Shenzhen products are sold around the world, after all. That’s why the school’s faculty include those with doctoral degrees not just in user experience and industrial design but also music composition and cultural history

As in the SDIM, the School of Design emphasizes intensive project-based learning. Early in this academic year, students designed cardboard furniture for kindergarteners, a process that introduced them to material properties, strength and usage as well as client feedback from a class of 4-year-olds. Students are now working with a major Shenzhen bicycle manufacturer to design handlebar grips. That project will teach them about ergonomics, additive manufacturing, and 3D printing, among other lessons.

SUSTech has big plans for the School of Design. Graduate programs are in the works. And by the end of 2024, the university intends to spin off the school into a standalone institution — the Shenzhen Institute of Design and Innovation (SIDI) — on a new campus near the airport.

“What we’re trying to do is reflective of Shenzhen. We are moving at a faster pace, ...” Kvan said. “And that’s the goal: We’ll be tightly linked in all of our education to industry.”

This content was paid for by SUSTech and produced by Inside Higher Ed's sponsored content team. The editorial staff of Inside Higher Ed had no role in its preparation.